What is the correct color wheel for painting? It has been hotly debated for over a century, and everyone seems to have an opinion about what the "real" primary colors are. In the following post I hope to educate you about some of the theories about just which primary colors are the best to be used for painting, and why. Of course I also offer some of my own personal opinion based upon my own studies of color as well as my experience as someone who loves painting in oils.

The first problem we run into when looking at the various color wheels which can be used for painting involves something called Tertiary Colors. Tertiary colors are created when one mixes a primary color (Red, Yellow, Blue) with one secondary color (orange, violet, green). Generally these are the colors located next to them on the color wheel.

They often have specific names which can get quite exotic such as Sea Green, or Azure. This is because often designers want to come up with a cool name for a color so they can market it better. For various reasons painters have been taught and told to use the RYB color wheel. A few reasons include the fact that artist materials which are available now used to have toxic compounds in them. Now with the advent of dyes it is easier to synthesize a color such as cyan. The one thing to remember however when using these colors is that dyes will fade with age, while real pigments (such as cadmium) have already stood the test of time for centuries.

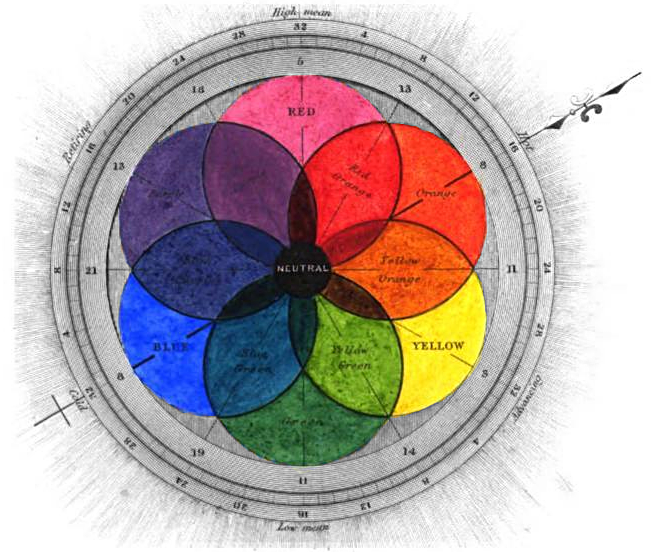

First we will be focusing on the Red/Yellow/Blue color wheel which is most often used by painters. In the color wheel above the Tertiary Colors shown are Yellow Green, Blue Green, Yellow Orange, Red Orange, Red Violet, Blue Violet, and Blue Green. This was widely believed to be standard colors to use for quite some time, and is still often used in Art Education up to this day.

An RYB color chart from George Field's 1841 Chromatography; or, A treatise on colours and pigments: and of their powers in painting

Back in the 18th century the theories surrounding color theory were cemented in the idea that the RYB (Red/Yellow/Blue) was the way to go. These theories have since changed over the years, however the RYB color model is still often used in teaching painting, and color theory up to this day.

These theories were enhanced by 18th-century investigations of a variety of purely psychological color effects, in particular the contrast between "complementary" or opposing hues that are produced by color afterimages and in the contrasting shadows in colored light.

During the 18th century the theory of the RYB model was furthered by two great thinkers. They were Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and Michel Eugene Chevreul. They were both transfixed by what is called the Psychological effects of color, and obsessed with how our eyes perceive color. One of the main things they observed was how complementary colors (that means they are opposite each other on the color wheel) created afterimages in our brains when they were "burned" into our eyes. They were also interested in why shadows in colored light would create contrasting shadows. You can download Goethe's The Theory of Colors here as I've uploaded it to this site. It is in the creative commons so there it has no copyright and is in the Public Domain.

After Goethe and his treatise on color, scientists moved away from the RYB color wheel and shifted towards a color wheel which most everyone sees every day. This is the Red, Green, and Blue (RGB) model which still dominates a lot of media to this day (Hint: It's how your TV works). To understand how this color wheel operates we need to go back to the previous lesson, and further examine how different lights makes different colors as opposed to how pigments (or physical mixtures of color) differ.

In the previous lessons we have talked about Additive and Subtractive colors. Forgive me if I wasn't clear enough before, but these lessons are meant to be sequential, and therefore sometimes I will withhold information so you can absorb it at different rates.

To put it simply, Additive Color is created by adding color. How do we add color? Well, by using light. That's why if you get up close to a TV set you will see tiny little bars of Red, Green, and Blue. Learning about additive color is particularly important for those who use a computer to create their imagery, as they are dealing with a medium that is essentially based upon the glow of a computer screen. Now, what happens when that person decides he wants to print out the image on his screen? The answer is that he will need to deal with another color wheel when the image is printed from a computer screen onto a piece of paper! This is because a piece of paper doesn't glow, it's reflecting light from a light bulb or the sun. As we discussed previously, an object doesn't hold a certain color because it reflects it, it is a certain color because it absorbs all the other colors in the spectrum. Hence the term, subtractive color.

So we, as painters, aren't painting with light, we're painting with paint. Hence, we need to use a color wheel which is specific to our needs. Let's take a look at the two different types of color wheels. Check out the first one below. This is a classical color wheel which utilizes Red, Yellow, and Blue as the primaries.

There's some nice oranges and violets in there right? Oh? What's that, you want them to be brighter and more vibrant? Well, then you can use the Cyan, Magenta, and Yellow color wheel below. CMYK is the color wheel which is utilized in printing, and has generally been regarded as the "true" set of primaries.

But there's a few problems with this color wheel. Mainly, it doesn't exist in nature (as in, natural pigments) as readily available as the colors which have been used for thousands of years. However if you want to oil paint with Cyan, Magenta, and Yellow then you can. But if you believe that oil paints will mix similarly to a printing machine then you're fooling yourself. As you have probably already learned, different colors and different pigments have different strengths and weaknesses.

By this I mean every color has different properties. In the printing process CMYK(K stands for black) are often used in transparent glazes. For instance, in order to make red in in CMYK printing you first print a tiny little magenta dot, and then on top of that dot is a yellow which is semi transparent. That's how you make red. Now with oil paint let's say that you want to paint a giant red object. If you were painting by utilizing the CMYK printing model you'd have to first paint an entire layer magenta, wait three days, and then on top of that you would glaze a bit of yellow on top of it to get your red. So yes, it is possible to paint with CMYK, but the simple answer is that it would simply take FOREVER to finish a painting, because we're not machines, and paint takes a long time to dry.

So what do we do as painters? Which color wheel should we use? I would suggest that you (that's right, you) find a palette that you enjoy working with. Limit it to no more than 10 colors, and get used to it. It takes a long time to learn how to properly mix and see color so find a palette that you feel comfortable manipulating. I know for me I like to use Cadmium Red Medium, Cadmium Yellow Medium, Pthalo Blue, Pthalo Green, Alizarin Crimson, Yellow Ochre, Ultramarine Blue, Raw Umber, Permanent Violet Medium, and Titanium White. And that's what I've used for numerous painting tutorials that I've done. It's a hybrid of both CMYK as well as the Old RYB models. With RYB it can be difficult to make a nice brilliant violet as well as green. So what do you do? You buy them :) And if you want to try to paint with Cyan, Magenta, and Yellow then you can. These colors are generally referred to as Process Blue, Process Red, and Process Yellow. They're dyes so they won't last as long (meaning they'll fade faster) as the classical pigments but they could be interesting to experiment with. For me? I'll stick to Cadmiums, Ultramarine, Titanium, and Cobalt. There's a reason why they've been around for thousands of years.